Printmaking explained by Kawase Hasui

Share

This article presents and quotes from Brigitte Koyama-Richard's excellent book on Kawase Hasui. Many of the images are from the Ota City Folk Museum, rare pieces that I've never had the chance to see elsewhere.

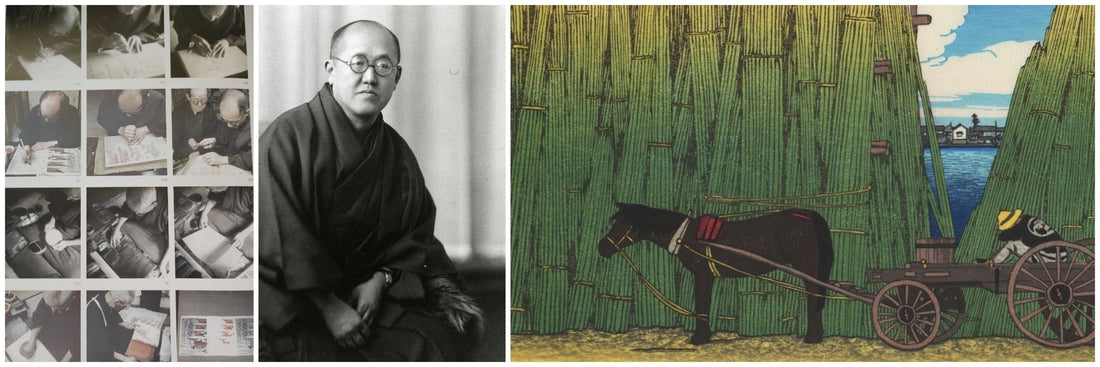

Shin Hanga prints are created using the same process as those from the Edo period, relying on collaboration between the publisher (hanmoto), the painter, the engraver, and the printer. Unlike traditional prints, which were often seen as recreational or educational objects, Shin Hanga prints were primarily artistic creations. This artistic revival was spearheaded by Watanabe Shôzaburô, a visionary publisher and key figure in the movement.

The documentary A Life in Prints (Hanga ni ikiru) highlights the close relationship between Watanabe, the painter Kawase Hasui, the engraver Maeda Kentarô, and the printer Ono Gintarô. While Hasui remains the most well-known today, the meticulous craftsmanship of his collaborators deserves recognition.

Step 1: The Preparatory Drawing

Kawase Hasui traveled extensively across Japan, searching for inspiring landscapes, which he sketched in black pencil, sometimes adding touches of color. In the evenings, he refined his drawings, transferring them onto a larger sheet of paper matching the standard ôban format (36 × 24 cm) used for prints. Once satisfied, he presented his sketch to Watanabe, who assessed its commercial potential. Producing a print was a significant investment for the publisher, who had to pay the artisans in advance and finance materials such as paper, wood, and tools.

Once approved, Hasui meticulously traced the main lines of his drawing in Indian ink onto a thin sheet of Japanese paper, which he then passed on to the engraver.

Step 2: The Engraving Process

Master engraver Maeda Kentarô spent about two weeks carving the first complete woodblock (omohan). He used cherry wood, a hard material with a fine grain that expanded minimally when humidified and shrank little when dried, ensuring exceptional precision. Watanabe sourced these woodblocks years in advance, allowing them to dry for three years before use.

The engraver coated the block with a traditional rice-based glue (wanori or yamatonori) and pressed the traced drawing onto it. By gently rubbing the thin paper with his fingers, the Indian ink lines transferred onto the wood while the paper disintegrated, leaving the image ready for carving. This process was irreversible.

Maeda Kentarô first incised the contours of the drawing, then carefully removed the surrounding wood to create relief. The precision of his carving determined the beauty of the final print. Once the first block was complete, he used it to create monochrome test prints, which Hasui then hand-colored to indicate the exact hues required for the final artwork.

The engraver then carved additional blocks, each corresponding to a different color. To ensure perfect alignment during printing, he added two registration notches (kentô) on each block: one in the lower right corner (kagi kentô) and another higher up on the same side (hikitsuke kentô).

Step 3: Printing the Artwork

The printer carefully prepared his tools, including his baren, a handmade tool composed of fine strips of woven bamboo bark. He crafted it himself by layering paper, lacquer, and fine fabric before inserting the woven bamboo inside.

Beside him, he arranged his water-diluted pigments and sheets of Echizengami paper, pre-moistened with dôsa (a mixture of animal glue and alum). Traditionally, pigments were derived from minerals or plants, but by the late 19th century, synthetic dyes with more vibrant hues became available.

The printer also prepared his Indian ink, which came in solid sticks and was essential for outlining the artwork. He moistened the engraved blocks using a brush made from horsehair, which had been burned and polished on a sharkskin surface to prevent warping.

Colors were applied gradually, from the lightest to the darkest shades. Each sheet of paper was aligned with the kentô notches and pressed against the engraved block. Using the baren, the printer rubbed the paper in circular motions to ensure the pigment transferred evenly.

Watanabe Shôzaburô also introduced a new technique called Gomazuri, which deliberately left visible circular traces of the baren on the print, adding a distinctive texture to Shin Hanga works.

Seated cross-legged before his slanted wooden table (suridai), the printer worked meticulously, constantly checking for misalignment of colors. Once all the layers were perfectly printed, the Shin Hanga print was complete—a testament to patience, precision, and artistic mastery.

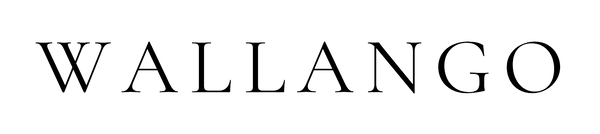

Images from the film Color mokuhanga no dekiru made in the book Kawase Hasui, le poète du paysage by Brigitte Koyama-Richard

The archives of the Ota City Folk Museum

May 3, 1955 On this day, Hasui began painting the original canvas for his masterpiece “Hiraizumi Konjikido”.

Kawase Hasui - Hiraizumi Konji and preparatory drawing

Order a high-definition reproduction of the print Hiraizumi Konji in our store

Hasui Kawase « Shiobara Hatashita » 1945 and preparatory drawing from sketchbook n°66 (source : Ota City Folk Museum)

Kawase Hasui Ibaraki Christian School Lawyers' House and preparatory drawing (source : Ota City Folk Museum)

Kawase Hasui - Miho no Matsubara and preparatory drawing

Order a high-definition reproduction of the print Miho no Matsubara in our store