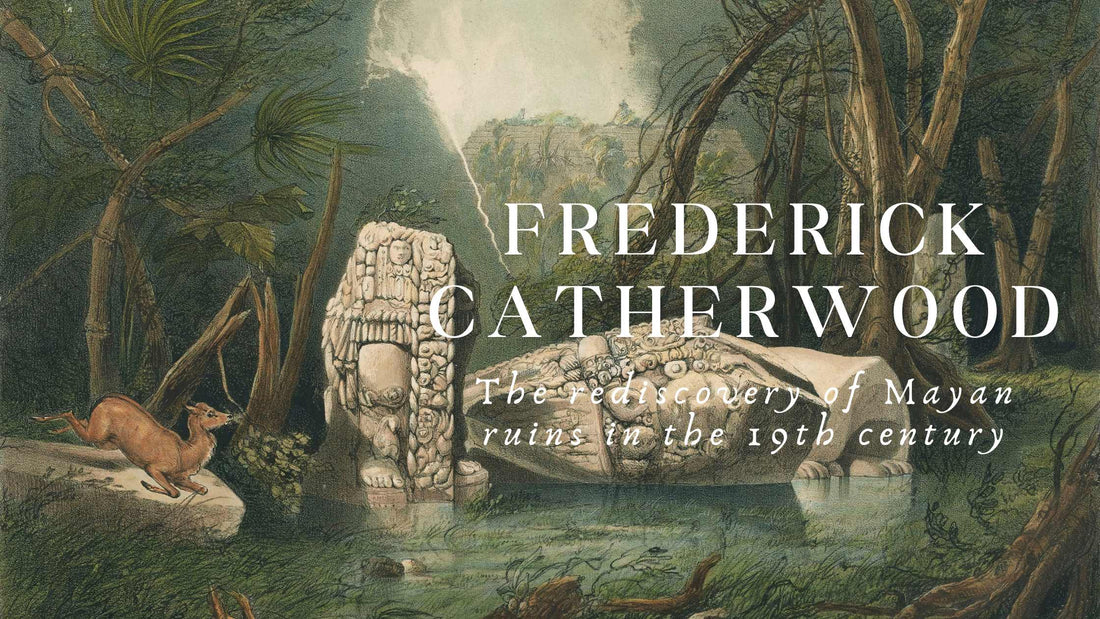

Frederick Catherwood : In search of America's lost cities

Share

Finding America's lost cities

In 1839, John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood embarked on their first expedition to Central America. Their groundbreaking exploration introduced many major Mayan cities to the world. Years of research and immense effort were required to uncover and document temples, stelae, and artifacts, shedding light on this ancient civilization. During the adventure, they faced severe challenges such as malaria, yellow fever, and political upheaval. Their iconic work, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan, combined with Catherwood's lithographs, remains invaluable, as many described sites and objects have since been lost to time.

Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan (1949 edition)

First expedition 1839-1840 :

Copán, Honduras

Stephens and Catherwood left New York on October 3, 1839 and reached Belize on October 30, 1939. They then hired a guide familiar with the jungle and some ancient archaeological sites. When they arrived in Copán, they discovered large Maya buildings overgrown with vegetation. The abandoned sites are difficult to access, the tree roots have displaced stones, the stelae are overturned and covered with moss, but they understand that they have penetrated an immense archaeological complex, which they will set about describing. Frederick Catherwood uses the camera lucida to capture the intricate details of Mayan architecture, from imposing pyramids to delicate sculptures. This drawing tool enabled him to project images onto paper with remarkable precision, guaranteeing his depictions a scientific accuracy unheard of at the time.

The camera lucida is an optical device used by artists and scientists to assist in drawing. Patented by William Hyde Wollaston in 1807, it utilizes a prism to superimpose the image of a subject onto a drawing surface, allowing the user to trace the outlines and details with accuracy. Unlike the camera obscura, it is portable and doesn’t require darkened rooms or screens, making it more convenient for fieldwork. The camera lucida was widely used in the 19th century for scientific illustration and topographical sketches.

The camera lucida is an optical device used by artists and scientists to assist in drawing. Patented by William Hyde Wollaston in 1807, it utilizes a prism to superimpose the image of a subject onto a drawing surface, allowing the user to trace the outlines and details with accuracy. Unlike the camera obscura, it is portable and doesn’t require darkened rooms or screens, making it more convenient for fieldwork. The camera lucida was widely used in the 19th century for scientific illustration and topographical sketches.Frederick Catherwood illustrations from Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and the Yucatan (1841) and Incidents of Travel in the Yucatan (1843) :

Quiriguá, Guatemala (first expedition)

Plate 6, General View of Palenque

This image shows the Temple of Inscriptions (center) and the Palace (left), two iconic structures from Palenque in Chiapas, Mexico. Surrounded by dense jungle, these ruins had been nearly reclaimed by nature. Catherwood found the dense foliage challenging to capture in his drawing. Stephens and Catherwood viewed the overgrown state as a sign of neglect by locals, which led them to attempt securing ownership of the ruins. However, their efforts were interrupted by local opposition, asserting ancestral rights and rejecting the explorers’ perception of indifference toward the ancient site.

Uxmal, México (first expedition)

Plate 10, Archway, Casa del Gobernador, Uxmal

This lithograph shows the north façade of the House of the Governor in Uxmal, representing the Puuc architectural style, which was created without metal tools. Catherwood focuses on part of this massive structure, emphasizing its intricate upper mosaic façade made of thousands of handmade pieces.

The building is adorned with numerous Chac masks (representing the rain god) and serpent motifs. Catherwood highlights these features in two separate lithographs from his time in Uxmal. Interestingly, he includes a snake in the foreground, potentially symbolizing its importance in Maya culture.

Sabachtsché, Yucatan (first expedition)

Well and building at Sabachtsché (Yucatán), watercolour

In this drawing, Catherwood emphasizes the contrast between the everyday life of 19th-century Maya and the grandeur of their ancient ancestors. Workers from Sabactsche, a small Yucatán village, gather around a well, depicted in vibrant colors, symbolizing a lively and organized society. However, the ancient structure in the background, illuminated to stand out, overshadows the activity, suggesting a superior, lost civilization. This visual contrast reflects Catherwood's recurring theme of comparing the achievements of the Maya's past with the contemporary world, raising questions about the value of different eras.

Labná, México (first expedition)

Plate 19, Gateway at Labnah

In this image, the indigenous figures subtly direct the viewer’s attention to the grandeur of the Maya ruins. Their gaze and activities, such as two men working on the structure in the background, naturally lead the eye toward the ancient edifice. The relaxed posture of the workers contrasts with the significance of the ruins. Notably, the corbel vault, with its flat peak, stands out at the center, unlike Roman arches. This structure, like others in Labnah, represents the decaying yet proud legacy of a mysterious civilization, as highlighted in Stephens’ Incidents of Travel.

Chichén Itzá, México (second expedition)

Plate 22, Teocallis, at Chichén-Itzá (Kukulcán Temple)

Tulum, México (second expedition)

Plate 23, Castle, at Tuloom :

Frederick Catherwood fine art posters :