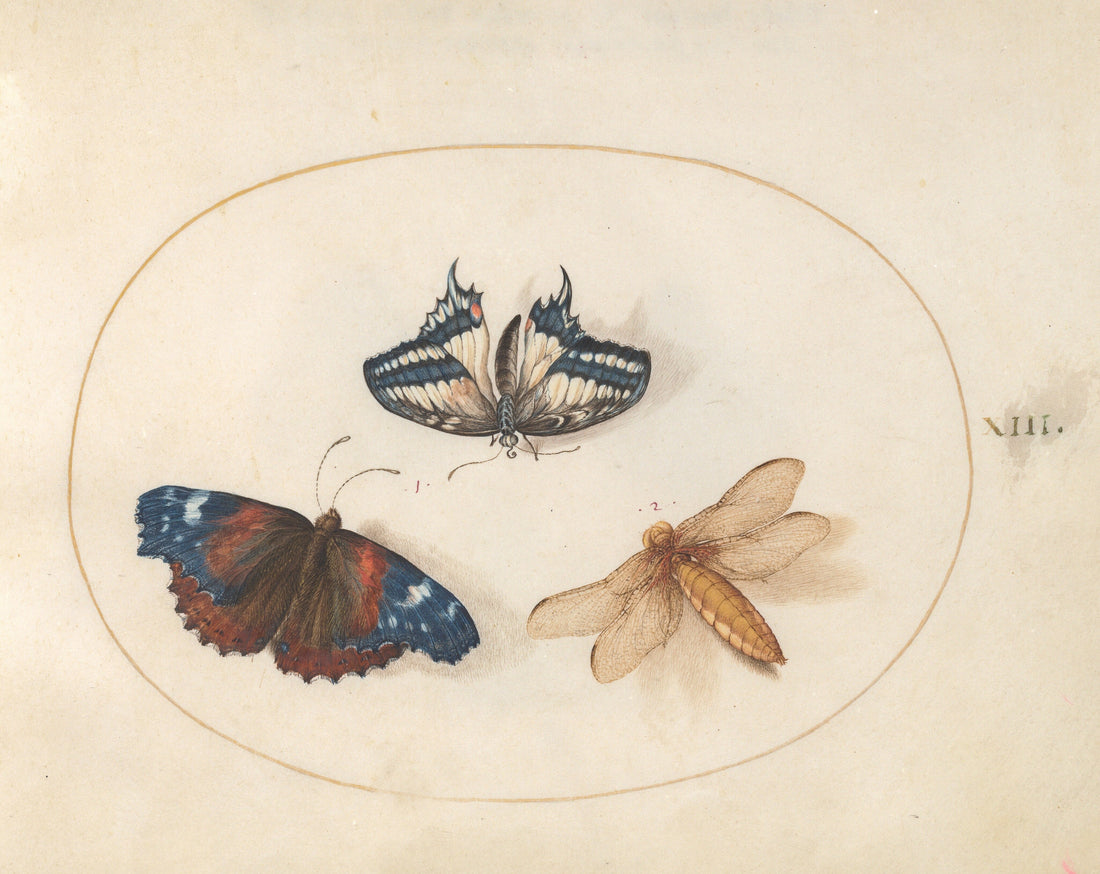

Joris Hoefnagel and The Four Elements

Share

The Four Elements is one of the principal manuscripts of Joris Hoefnagel (1542-1600). It consists of four volumes, each depicting a group of creatures associated with one of the elements :

- Animalia Rationalia et Insecta : IGNIS (Human wonders and insects - Fire)

- Animalia quadrupedia et reptilia : TERRA (Quadrupeds and reptiles - Earth)

- Animalia aquatilia et conchiliata : AQUA (Fish and shells - Water)

- Animalia volatilia et amphibia : AIER (Amphibians and birds - Air)

As we shall see later, the choice of this order to present the different kingdoms is not insignificant.

Plate 25: Blue Underwing Moth and Spurge Hawk Moth, c. 1575/1580

A key monument of Netherlandish art of the sixteenth century, the Four Elements is a response to older trends in Netherlandish nature painting and a catalyst for the development of the genres of the flower piece and animal painting in the Netherlands and Central Europe. It is also one of the earliest works on modern entomology, and a unique natural history book in general.

Hoefnagel had chosen 'natura magistra' (nature his teacher) as his motto. It reflects his interest in the realistic depiction of nature. He made a start with his miniature drawings of animals before he left Antwerp. It is on the strength of these early miniatures that he was appointed by the Dukes in Munich. Gradually these natural history were organised into a four-volume manuscript (various folios dated from 1575 to 1582 in various museums including the National Gallery of Art, Washington, the Kupferstichkabinett Berlin, the Louvre, Paris and various private collections).

Art gallery from all four volumes

Plate 23: Hummingbird Hawk Moth, Butterflies, and Other Insects around a Snowberry Sprig

Plate 28: A "Tartarine" (Barbary Macaque?) with Fruit and a Snail

Animalia Aqvatilia et Cochiliata (Aqva)- Plate I

Plate 34: Bird of Paradise with Mereganser and Grebe

Questions raised by The four elements

Ignis : The primacy of man and insects in creation

Why did Hoefnagel choose to present man in the same volume as insects, and why did he associate fire with them?

The theory of the elements goes back to the time of Aristotle and his conception of the universe as being divided into two parts: the perfect Cosmos made up of Ether, in which the immutable stars gravitate, and the changing and corruptible sublunary world, made up of a mixture of Fire, Air, Water and Earth, elements initially separated into concentric spheres from Earth to Fire.

This organization of the cosmos is an order of things that logically organizes animals: the three elements of Earth, Water and Air correspond respectively and logically to terrestrial animals (quadrupeds and reptiles), aquatic animals (including crustaceans and shellfish) and birds.

But what about Fire, positioned first in an order that owes nothing to chance ?

Unlike the other elements, which represent the natural habitats of the kingdoms represented, fire is an element that operates through its symbolism. By associating his insects with fire, Hoefnagel links them to the most exceptional element, the element associated with generation and dematerialization, the most protean, the most dynamic, the most unfathomable and, in pre-modern Europe, the most marvellous.

At the time, insects were still largely unknown. Since ancient times, it has been thought that some of them are born by spontaneous generation. The link between egg, larva, nymph and imago was poorly understood.

Before anyone else, Hoefnagel seems to have seen the insect world as a realm worthy of interest. The multitude of species represented in Ignis like never before will be an authority among entomologists for decades to come (the first known scientific publication on insects was Aldrovandi's in 1602).

Joris Hoefnagel - Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (Ignis): Plate V Stag Beetle

An inner dialogue and Praise to the Creator

The layout of the four volumes is similar: the watercolor and gouache illuminations are in the center, with a maxim or literary excerpt above and/or below the image. The inscriptions come from the Bible, from ancient authors such as Ovid, or from humanists such as the maxims of Erasmus

If Hoefnagel invites us to contemplate creation through his work, it is also a question of summoning themes through inscriptions. This device is singular in that it manifests both public praise for the divine Creator and access to the author's interiority, which is reflected in his choices.

At the head of each volume is an inscription of biblical origin.

Ignis :

Source: Psalm 103 [104] verse 4 qui facis angelos tuos spiritus et ministros tuos ignem urentem : he makes his messengers winds, his ministers a flaming fire.

Terra :

Qui fúndasti terra súper stabilitatem túam ; This is verse 5 of the Vulgate He established the earth on its foundations, It will never be shaken

Aqua :

Abissus sicut vestimentum amictus terrae super montes stabunt Aquae.This is verse 6 of the Vulgate : You covered it with the deep as with a garment, The waters stood still on the mountains

Aier :

Qui ponis Núbem, ascensum tuum : He takes the clouds for his chariot, He advances on the wings of the wind

The sources of its imagery

The manuscript should be interpreted as an effort to achieve consummate mimetic mastery of nature. This interpretation offers solutions to three further sets of problems. The first concerns basic information on the manuscript-the sources of its imagery, the reasons for its execution, and the meaning of its curious and eclectic format.

Relation to floral still life and animal painting

Still Life with Flowers, a Snail and Insects, Watercolor, gouache,and shell gold on vellum

The Four Elements' relation to floral still life and animal painting. The emergence of these genres, often conceived of as a beginning, it also the result of the gradual fragmentation of the concept of nature in Netherlandish art, with the Four Elements marking the midway point in this development.

An idiosyncratic genius with neither antecedents nor followers

Finally, there is the problem of understanding Hoefnagel's oeuvre. Hoefnagel is thought to be an empiricist, an emblematist, and an idiosyncratic genius with neither antecedents nor followers. Understood as an attempt to achieve perfect imitation of nature, the Four Elements emerges as the pivotal work of his oeuvre, lending unity to his multifaceted art.

Joris and Jacob Hoefnagel - Allegory on Life and Death

Interested in a reproduction on museum paper ?