From chaos to divinity: The Dragon’s Ever-Shifting Role

Share

The dragon fascinates, terrifies, and inspires. A mythical creature that has endured through time and across cultures, it does not, however, carry the same meaning wherever its mystical breath reaches. In the West, it is a monster, a beast of chaos and fire, often defeated by a hero in shining armor. In the East, it is more complex—both a celestial force of wisdom and a formidable, untamed power. Revered as a master of water and nature, it is not always benevolent; it can be a bringer of storms, a test of strength, or a guardian whose favor must be earned. Two opposing yet intertwined visions of the same myth, much like the dragon and the tiger in Asian tradition—locked in eternal struggle, neither able to exist without the other.

The Dragon in the West: A Monster to Be Slain

In Western culture, the dragon is the lurking beast, the guardian of treasures or the destroyer of kingdoms. It often represents evil, raw and untamed power that a hero, sword in hand, must vanquish to restore order.

From Antiquity, dragon-like creatures appear in European mythology. The giant serpent Python, slain by Apollo, and Ladon, the guardian of the Garden of the Hesperides, foreshadow this eternal struggle between man and beast. In Christian tradition, the dragon becomes an incarnation of the Devil. Saint Michael slays the dragon in a celestial battle, and Saint George rescues a city by piercing the creature with his lance. The West has made it a symbol of the ultimate obstacle, the final test to overcome.

Medieval tales perpetuate this image. In Arthurian legends, dragons often signal war or disaster. And what would fantasy be without its nightmare-inducing dragons? Smaug, in The Hobbit, embodies greed and destructive power, while the dragons of Game of Thrones serve as weapons of war—mighty yet unpredictable.

In short, in the West, the dragon is a challenge, a threat, a guardian of forbidden treasures or knowledge. It cannot be tamed; it must be defeated.

This painting, "Saint Michael Vanquishing the Dragon", created by Raphael around 1503-1505, illustrates one of the most recurring motifs in Christian iconography: the victory of Good over Evil, embodied in the battle between the archangel and the dragon.

In Christian tradition, the dragon symbolizes demonic forces, chaos, and corruption. It is the enemy to be defeated, often depicted as a monstrous, hybrid creature reminiscent of the chimeras of medieval bestiaries. Here, Archangel Michael, leader of the celestial armies, triumphs over the beast by trampling it underfoot and raising his sword to deliver the final blow. His shield, marked with a cross, reinforces the idea of a divine and inescapable mission.

This Western vision of the dragon contrasts with that of the East, where the creature is not solely a symbol of evil. In Asian art, the dragon is often an ambivalent force—both a guardian and a destroyer, representing the power of natural elements. While the West portrays its destruction, the East emphasizes the necessity of coexisting with it.

Raphael’s painting thus follows a tradition in which the dragon is an adversary to be tamed and annihilated, reflecting a dualistic conception of the world where Good and Evil engage in an uncompromising struggle.

The Dragon as a Benevolent and Protective Creature

- The Red Dragon of Wales: The Welsh flag features a red dragon, a symbol of strength and protection. According to legend, this red dragon fought and defeated a white dragon, representing the invading Saxons, thus affirming the sovereignty of the Britons.

- Cadmus' Dragon: In Greek mythology, Cadmus slays a sacred dragon of Ares, but to atone for his act, he must serve the god of war. From the dragon’s teeth spring the Spartoi, the ancestors of Thebes. Here, the dragon is not an evil monster but a sacred being.

Vortigern and Ambros watch the fight between the red and white dragons: an illustration from a 15th-century manuscript of Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain.

The Dragon as a Symbol of Wisdom and Knowledge

- Fáfnir in Norse Mythology: While Fáfnir is a greedy and dangerous dragon, he also possesses formidable wisdom. In the Volsunga Saga, Sigurd drinks his blood to understand the language of birds and acquire knowledge.

- Dragons in Occultism and Alchemy: In alchemy, the dragon often symbolizes the primordial forces of nature and the process of transformation. The ouroboros dragon, which devours its own tail, is a symbol of eternal cycles and infinity rather than malevolence.

The Dragon as a Companion or Ambivalent Being

-

Dragons in Fantasy Literature:

- In Eragon by Christopher Paolini, dragons are majestic and highly intelligent creatures, bonded telepathically with their riders.

- In The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien, Smaug is a greedy antagonist, but other dragons in Tolkien’s universe are not necessarily evil.

- Game of Thrones also portrays dragons as powerful and dangerous but loyal to their master and carriers of great power.

The Dragon in the East: Wisdom and Divine Power

On the other side of the world, the dragon dances in the sky, bringing rain and prosperity. In Japan, China, and Korea, it is a force of nature, often benevolent, sometimes capricious, but never evil.

Japanese dragons are deeply rooted in the country’s mythology, but their meaning and significance are anything but fixed. These mythical beings are polymorphic, with a wide variety of forms and roles that evolve across different regions and stories. The Japanese dragon is not a singular, unambiguous figure but rather a dynamic and multifaceted creature whose interpretation varies based on time, place, and cultural influence. While heavily influenced by Chinese dragons—particularly the three-clawed, serpentine form—Japanese dragons also incorporate elements from Korean and Indian mythology, creating a rich tapestry of symbolism.

Commonly associated with water, these dragons are often revered as kami or deities of rain and rivers. Yet their shape, function, and symbolism can shift dramatically: some are benevolent, others are fearsome, and still others embody the unpredictability of nature itself. The fluidity of the dragon’s nature reflects the broader complexity of Japanese mythological traditions, where meanings are layered and mutable, offering a broader, more inclusive understanding of the world around them.

The Japanese ryū comes directly from the Chinese long, a celestial dragon that rules rivers, seas, and the climate. It is linked to gods and emperors, often depicted with a long, serpent-like body, floating among the clouds. No wings, no infernal flames—here, the dragon is associated with water, fertility, and cosmic balance.

Among the most famous myths is Ryūjin, the dragon king of the seas, who protects the ocean depths and grants magical pearls to heroes. Yamata-no-Orochi, however, is an exception: a malevolent, eight-headed dragon defeated by the god Susanoo, in a tale strangely reminiscent of Western legends.

Yamata-no-Orochi - Toyohara Chikanobu :

The kami Susanoo-no-Mikoto (god of storms) slays the eight-headed beast Yamata-no-Orochi. After slaying the beast, Susanoo found the sword Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi in one of the eight tails of the gigantic serpent.

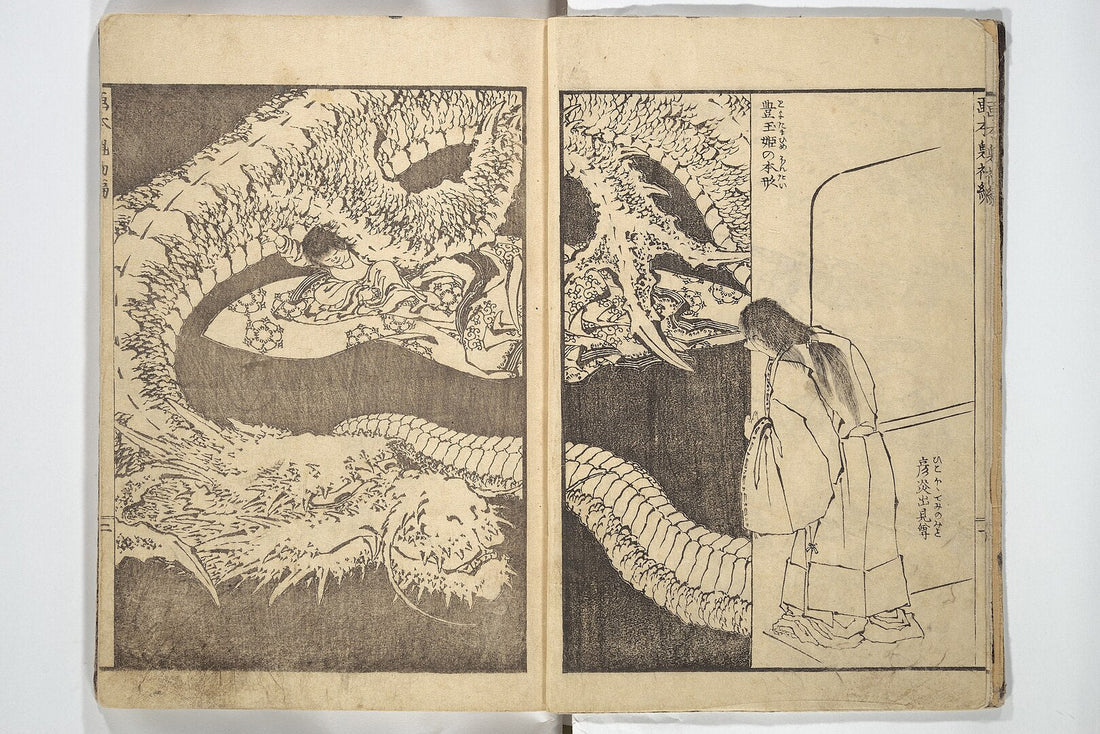

This striking ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi depicts the legendary story of Princess Tamatori (Tamatorihime), a pearl diver (ama) pursued by Ryūjin, the Dragon King of the Sea. Unlike the benevolent dragons often seen in Japanese art—guardians watching over temples and paintings—this dragon embodies a more menacing force. With its fierce expression and serpentine body, it surges through the waves, relentless in its pursuit. Here, the dragon is not a passive protector but an adversary, a being whose power must be reckoned with rather than simply revered.

In Japanese mythology, Ryūjin is the ruler of the ocean, dwelling in an opulent underwater palace known as Ryūgū-jō. He commands the tides and governs the creatures of the sea, sometimes appearing as a wise, benevolent deity and at other times as a vengeful force. In the legend of Tamatori, he is the latter—furious at the theft of his treasured pearl and summoning sea creatures to reclaim it. Kuniyoshi masterfully captures this moment of desperation and defiance, emphasizing the dynamic struggle between human courage and the overwhelming forces of nature.

Wani

Wani is a creature from Japanese mythology, often depicted as a dragon or sea monster. The term "wani" is derived from the kanji, which originally refers to a crocodile or alligator, based on its Chinese counterpart. In some contexts, it is also translated as "shark". Wani is typically associated with water, embodying the ferocity and power of aquatic creatures in Japanese folklore.

An illustration of Princess Toyotama, the daughter of the dragon king of the seas, who transformed herself into a wani to give birth to her son (1836).

Zennyo Ryūō (illustration : Hasegawa Tōhaku)

Zennyo Ryūō (善如龍王 or 善女龍王, meaning "goodness-like dragon-king" or "goodness woman dragon-king") is a rain-god dragon in Japanese mythology. In 824 AD, according to Japanese Buddhist tradition, the priest Kūkai summoned Zennyo Ryūō during a renowned rainmaking contest at the Kyoto Imperial Palace.

The Duel of the Dragon and the Tiger: Strength vs. Wisdom

Dragon and Tigers by Kanō Sanraku

One of the most famous representations of the dragon in Asia is its eternal duel with the tiger. In Taoist tradition and martial arts, these two creatures embody opposing yet complementary forces.

- The Dragon (ryū, 龍): A symbol of heaven, spirituality, wisdom, and fluidity. It represents invisible, guiding power.

- The Tiger (tora, 虎): A symbol of earth, physical strength, instinct, and direct combat. It is a wild and untamable beast.

Their battle represents the balance between intelligence and brute strength, between strategy and instinct, between heaven and earth. In art, this scene frequently appears in Zen paintings, woodblock prints, and traditional Japanese tattoos (irezumi). But this battle has no victor—it is the eternal cycle of opposition and harmony.

Two Visions of the Same Myth?

Why such a difference between East and West? Perhaps because, in Western thought, the dragon embodies a danger to overcome, while in the East, it is a force to understand. Where the West sees an enemy, the East sees a balance to maintain.

These visions seem irreconcilable, yet they tell the same story: humanity’s relationship with power. Should we fight it or tame it? Fear it or honor it?

The history of dragons is the history of humankind facing the unknown, confronting the mysteries of the world and forces beyond comprehension. And whether we battle it or revere it, one thing is certain—the dragon will continue to haunt us.