Gustave Doré and the Dark Poetry of La Fontaine’s Fables

Share

Published in 1867, Gustave Doré's illustrated edition of La Fontaine's Fables stands as one of the most ambitious publishing ventures of the 19th century. With over 200 engravings (including 85 full-page plates), Doré offers a striking visual dimension to the celebrated tales of Jean de La Fontaine.

But far from simple descriptive illustration, his compositions oscillate between meticulous realism and fantastical visions, establishing a fertile tension between the animal world, the human world, and an imagination that often summons imagery beyond the fables themselves.

Some scenes take on a dramatic, even tragic dimension, while others preserve a biting lightness or visual irony. Through his mastery of tone engraving, Doré skillfully employs chiaroscuro to create nocturnal, theatrical atmospheres that heighten the moral and symbolic nature of the fables.

This work fits within a long tradition of illustrating La Fontaine's Fables, notably marked by:

-Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686–1755), whose paintings from 1729 to 1734 were engraved for a 1755 edition. His refined, naturalistic style dominated 18th-century fable imagery.

-Jean-Jacques Grandville (1803–1847), who published a satirical and anthropomorphic version between 1838 and 1840, where animals reflect human society with biting irony.

In Grandville’s illustration for The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse, the rats are dressed as 19th-century bourgeois gentlemen, dining in an opulent interior. His anthropomorphic and satirical style places the fable in a contemporary social setting, highlighting the contrast between luxury and danger—embodied here by a cat in a housecoat—through humor and irony.

Doré, by contrast, favors a darker realism: his mice retain their animal form and move through starker, moodier environments. While Grandville satirizes and entertains, Doré emphasizes the fable’s timeless moral—better a simple life in safety than the perils of opulence.

The Making of Fables: Between Tradition and Innovation :

The texts themselves, written between 1668 and 1694, draw from an even older tradition: the ancient Greek fables of Aesop, a 6th-century BCE slave, enriched by Latin influences from Phaedrus and Eastern traditions. La Fontaine adapts these short moral tales to the language and society of his time, with a freedom of tone and stylistic richness that made them classics.

It is this centuries-old tradition that Doré reinvents with his sumptuous blacks, twisted landscapes, and expressive animals, giving the fables a renewed visual density that reshapes both their interpretation and their collective imagery.

Over time, however, the illustrator shifts from animal allegory to a deeply human and socially engaged retelling. This is especially evident in his final engraving for The Cicada and the Ant — available here as a fine art print —, where the cicada is portrayed as a poor yet dignified woman holding a musical instrument in the snow, while the ant, a distant bourgeois figure, remains sheltered inside her home. Beside her, two well-dressed children appear to belong to her household, reinforcing the image of an orderly, prepared existence. This realistic transposition introduces a dramatic and critical reading of the fable, in which emotion takes precedence over moral judgment.

The preparatory drawing—executed in pen, ink, wash, and white gouache on wood—reveals that Doré initially seemed to favor a more naturalistic approach, focusing on the insects themselves. The cicada, a true orthopteran, lies frozen in the snow before the sealed entrance of the ant’s den, in a stark and merciless scene.

This shift from bestiary to social realism encapsulates the essence of Doré’s approach: not merely to illustrate La Fontaine, but to reveal the tragic modernity embedded within his fables.

Fantastic Realism:

A subtle paradox runs through Gustave Doré's visual world for La Fontaine's Fables: the meeting of realism and the fantastic. At first glance, these two terms seem mutually exclusive. Yet Doré reconciles them with remarkable ease.

His animals are rendered with rigorous, almost scientific naturalism—reminiscent of Buffon's plates: every hair, paw, and beak drawn with anatomical precision. But this precision only intensifies the sense of unease produced by the settings: spaces where shadow, light, and dizzying perspectives create a supernatural effect.

This is not the fantasy of fairy tales, but rather a disruption of the familiar: the world appears coherent, yet it is quietly permeated by strangeness. This paradox mirrors the nature of the fable itself—a hybrid genre that uses animals to express human truths and turns everyday life into moral or political allegory. Doré fully embraces this duality: his images make visible the moral ambiguity of the fables, where reality is constantly threatened by the imaginary and the ordinary is charged with allegorical power.

A Dark and Poetic Romanticism: Tim Burton Before His Time?

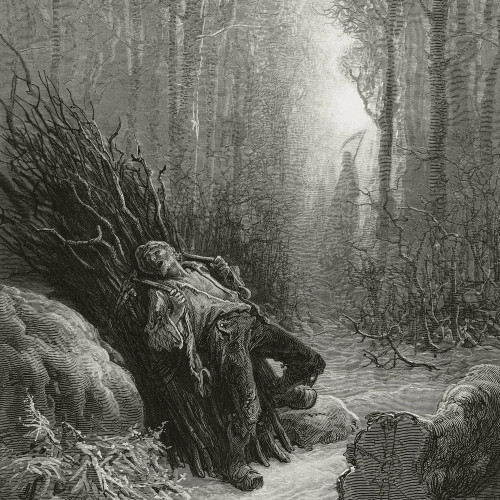

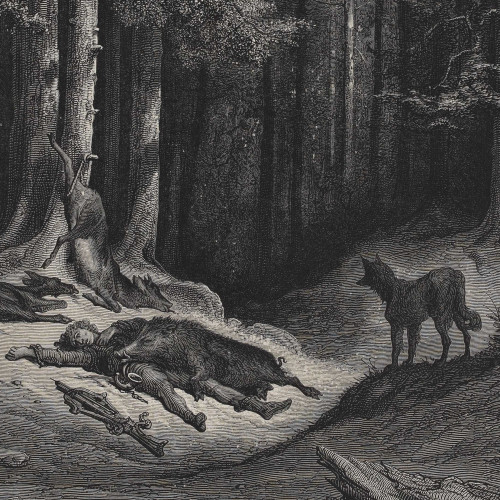

Doré's full-page illustrations for La Fontaine's Fables reveal an almost cinematic quality, where visual imagination outweighs narrative. Impenetrable forests, dramatic chiaroscuro, spectral moons, stormy skies: everything contributes to a dark romanticism, at the crossroads of meticulous realism and poetic fantasy. It's no wonder that these images evoke the world of Tim Burton, with recurring motifs—gnarled trees, solitary animals, frightened or contemplative silhouettes—that resonate with a now-popular gothic imagination.

This tension between near-scientific detail and supernatural settings fuels symbolic interpretation. For Doré, the forest is no mere background: it becomes a character, a place of ordeal, danger, and destiny—a motif that taps into ancestral fears. The hyperrealistic stag, monkey, or dolphin stands out against ominous landscapes filled with foreboding. "Eh! mon ami, la mort te peut prendre en chemin" ("Friend, death may take you on the road"), writes La Fontaine: Doré takes this line literally, engraving it in shadow.

These plates carry the same eerie strangeness as The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, a fantastical short story written by Washington Irving in 1820, where the woods host nocturnal hauntings and folk terrors. Arthur Rackham's 1928 illustrated edition of Sleepy Hollow gives the forest an almost supernatural presence—much like Doré's, though their styles differ. Doré explores dramatic chiaroscuro; Rackham favors twisted, haunted silhouettes. But in both, the forest is no longer passive decor: it is alive, conscious, and steeped in fear, imagination, and fate.

Highlights from the Plates:

The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse

This illustration echoes the genre of "sumptuous still life," inherited from 17th-century Dutch painters like Willem Kalf and Abraham van Beyeren. The lavish display of fine dishes and luxury food contrasts ironically with the country mouse's panic. The dramatic lighting and cluttered opulence evoke a nightmarish abundance, turning moderation into a visual morality tale bordering on the grotesque.

The Council Held by the Rats

In a dark attic, side lighting reveals a circle of rats. The composition recalls Adriaen van Ostade's rustic interior scenes, with warm shadows and textured surfaces. Yet Doré goes further, creating theatrical drama: the forced perspective heightens claustrophobia. The rats resemble a miniature cult, straight out of a fantasy film.

The Stag at the Pool

Here, the fantastic emerges through ambiance. The stag is rendered with naturalistic accuracy, but placed in a twilight forest. The fallen trunk in the foreground resembles a felled body—a symbol of impending doom. Stillness and beauty conceal tragedy: vanity becomes a fatal trap.

The Wolves and the Sheep

A monochrome, moonlit scene where terrified sheep face a pack of wolves. The symmetrical composition and eerie calm resemble horror cinema. The wolves' glowing eyes and full moon suggest primal fear—a pastoral Sleepy Hollow, charged with dread.

An Animal in the Moon

Absurd and poetic: scholars observe the moon from a gothic terrace. The animal seen is blurred, but the scene evokes German romantic engravings and Alfred Kubin's metaphysical fantasies. The animal becomes a metaphor for elusive truth—a cosmic fable.

The Oak and the Reed

This plate encapsulates Doré's dark romanticism. The stormy sky, tormented trees, and flooded ground evoke apocalypse. The shattered oak symbolizes sublime defeat, the forest a conscious entity, like in Snow White or Sleepy Hollow. The forest is now a character.

The Monkey and the Dolphin

Bestiary turns fantastic: a monkey rides a dolphin lost at sea. The stylized waves and frantic expression recall Goya's distorted figures or Fantasia-like chaos. A fable of absurdity becomes a dreamlike vision: humanity adrift in symbolic waters.

Conclusion:

With his illustrations for Fables, Gustave Doré does more than accompany La Fontaine's text: he unveils its deeper layers—the tragic, the grotesque, the ironic, and the wondrous. Between realistic bestiary and haunted landscapes, his images give visual form to an imaginary that still speaks to our fears, humor, and melancholy. They extend the fable into the realm of myth.

Discover the Collection:

🎨 Explore our art print collection of La Fontaine's Fables illustrated by Gustave Doré, faithfully reproduced to restore all the graphic power and poetic mystery of these timeless masterpieces.